Importance of Study design

Continuing from the previous edition of the newsletter on this topic, once there is clarity about the focus area of the study, it is important to have a research question (study hypothesis) in mind, as that will decide the design that would be best. Some examples could be:

1. Metformin + DPP4 has better glycemic control in those with BMI 25-30 kg/m2 than in those with BMI > 30 kg/m2

2. Metformin + DPP4 has better glycemic control when started at the time of diagnosis than when the 2nd drug is added later.

3. Metformin + DPP4 has better glycemic control in those with diastolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg than in those with diastolic BP> 80 mm Hg or Metformin + DPP4 abc gliptin has better glycemic control in those with diastolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg while Metformin + DPP4 xyz gliptin has better glycemic control in those with diastolic BP> 80 mm Hg.

4. Among patients who did not show response to Metformin or DPP4 monotherapy, more patients below 40 years of age were prescribed Metformin + DPP4 abc gliptin while those above 40 years were prescribed Metformin + DPP xyz gliptin.

5. Metformin + DPP4 showed improved glycemic control within 3 months in those with normal serum creatinine while the same results were seen in 6 months in those with elevated serum creatinine. 6. Metformin + DPP4 showed improved glycemic control in patients with no hyperlipidemia but not in those with high lipid levels.

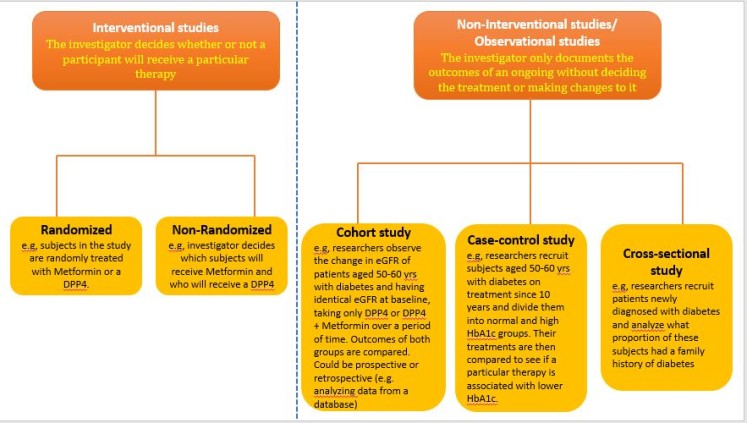

Study design: Among the examples of study hypotheses above, you can see that for question 5, at least 6 months’ data is required (longitudinal study). In example 4, data a single timepoint would suffice (cross-sectional study). For examples 1-3, the researcher would need to decide the cutoff time period that will be considered for the study (cohort studies). Example 6 compares the outcomes in those with the presence of a particular risk factor vs those who do not have that risk factor. (case-controlled study).

Let us now look at prospective studies. For ease of understanding and continuity, I will take the same example as that used above i.e., you wish to publish a study that aims to explore whether metformin still plays an important role in diabetes management in the era of DPP4s. We saw how a retrospective study design on this topic can be made to stand out from the existing studies, so as to have a good chance of an indexed journal being interested in publishing it. With the same example, we will see how a publication-worthy prospective study can be designed and more importantly, the pitfalls to avoid. First, some basics about the types of prospective studies: Prospective studies can be interventional or non-interventional. As the terms suggest, in an interventional study, the treatment might be changed during the course of the study based on a pre-designed plan in the protocol, or it might be changed based on certain outcomes. In non-interventional studies, the same treatment would continue throughout the duration of the study. One more type of non-interventional study is a cohort study that recruits people with a similar condition (disease and/or treatment) and collects information about them for a number of years. If the study has 2 or more arms (as most prospective studies do), another aspect that needs to be considered is patient allocation. In this regard, double-blind studies with random allocation are considered as the highest level of evidence and are more likely to have higher acceptability.

So, in a prospective study that aims to explore whether metformin still plays an important role in diabetes management in the era of DPP4s, the examples of the above types of prospective studies could be:

A study with subjects recruited and allocated to 2 arms: one group is administered only DPP4 and another administered DPP4+Metformin, and the outcomes followed over say 2 years. This would be a prospective, non-interventional study.

Subjects are recruited and allocated to 2 arms: one group is administered only DPP4 and another administered DPP4+Metformin. However, after 12 weeks of treatment, if the HBA1c level is more than 6.5, another drug is added. The drug might be pre-specified in the protocol or might be at the discretion of the treating physician. This would be a prospective, interventional study.

A study where all subjects in one group are on DPP4+Metformin and the other group on DPP4 alone and are followed over a long term e.g., 10 years or 20 years to see how many patients in each group develop adverse outcomes associated with diabetes, like myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, etc, would be a cohort study. In each of the examples, the subjects might be randomly or non-randomly allocated to the 2 arms depending on certain baseline criteria defined in the protocol. Again, these can be single-blind or double-blind, wherein the researcher, as well as the patients, do not know what drug is being administered, while the person who is treating the patients is not aware of the study, so that there is no bias in which patients gets what treatment.

So with the same study (better glycemic control with a combination of DPP4 with Metformin rather than DPP4 alone) being conducted retrospectively, we saw above, what could be the pitfalls that need to be avoided. When the same study is planned to be conducted prospectively, the do’s and don’ts are somewhat different. I am listing below a sort of checklist that needs to be considered before planning a prospective study so that after all the effort it is not rejected by the journals due to a flaw in the design. What is your study hypothesis (research question) and what data is already published from previous studies? I have explained these with detailed examples above; hence, will avoid repetition here.

Why do you want to do a prospective study? This is an important question because there are many ethical and legal factors involved apart from the time and cost. Assuming the time and cost factors are taken care of, what is the contribution this research will make to the existing literature for which it is worth performing the study despite the ethical and legal challenges? Examples of such concerns could be – obtaining informed consent from the patients, possible legal implications in case of any serious adverse events, insurance cover for the patients is required in some countries for prospective studies, justifying the intervention in case of interventional studies, justifying the random allocation to different treatment arms, and others. Is this study likely to bring out something new which could have future implications in the understanding/treatment of the disease and/or use of certain drugs? Hence, minute scrutiny of all research on the topic that is already available, what are the gaps in existing literature, and your research question becomes absolutely essential. At this stage, it should also be decided as to what patient profiles to the minutest details for inclusion can you define that will make your study different from those in the existing literature.

In the next edition, we will look at the importance of the sample size and statistical analysis plan and begin with some aspects of actually writing a manuscript.