Part I Why do most research manuscripts get rejected by leading medical journals?

This topic has been discussed to death; yet, it lives on. Undoubtedly, the objective of every researcher is to publish the results of the research, given the tremendous labor that goes into every clinical research. Besides, it is through sharing of research outcomes that medicine has come this far and continues to scale newer milestones. The current COVID-19 pandemic has driven home this message loud and clear even among the general population. Nevertheless, a minuscule number of submitted manuscripts submitted to the leading indexed journals see the light of the day. That said, the number of articles that do make it to the publication stage every year is humongous. A September 2018 report by University World News stated, ‘No one knows how many scientific journals there are, but several estimates point to around 30,000, with close to two million articles published each year.’ That is indeed a HUGE number. What is it then that cuts the ice? The list of reasons for rejection is long, and the common reasons that come to mind are in fact a small proportion of the causes for rejection. While there have been numerous articles over the years listing these causes for rejection, it might be helpful to look into each cause with some real-world examples. I have not listed some very obvious reasons like lack of ethics approval, lack of patient consent, and plagiarism because I think we have reached a stage where every researcher is aware of these laws, and the precondition of every journal that the researchers abide by these laws. Furthermore, it is assumed here that the manuscript is not outside the scope of the target journal. These mandatory tenets being met, we will look at what are the reasons for rejections. We will look at each factor listed below in detail, with some real-world examples. These, I hope, will help researchers right from the planning stage, to ensure that their research has a good chance of getting published.

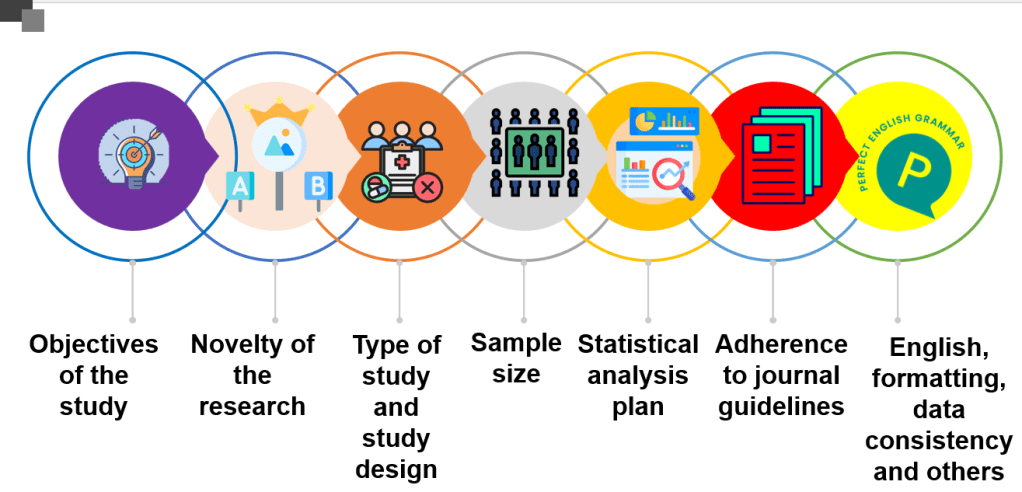

The following issues will be discussed in this series: Objectives of the study, type of study, study design, sample size, statistical analysis, the novelty of the research, non-adherence to the journal guidelines, and miscellaneous causes like formatting issues, inconsistent data, and others.

Study objectives and type: Perhaps, the commonest yet most overlooked causes for rejection are the study objectives and design. Several factors need to be considered before the objective(s) and design/type of the study are decided. Objectives and study type and design go hand-in-hand and cannot be discussed exclusively from each other. What often happens is that researchers either have data that they wish to get published as a retrospective study (because I have a good and large amount of data, why not publish it!), or they observe some trend in their clinical practice and think this can be conducted as a prospective study and published. However, in reality, these are endpoints and not starting points for a study. I will start with a simple example that all of us can relate to, and follow the same example to see how the objectives and study type/design need to be planned. Please note here that this is a hypothetical example and the data mentioned regarding the outcomes is not necessarily true. Let us say you wish to publish a study that shows metformin still plays an important role in diabetes management in the era of DPP4s. You might already have the data of several patients on metformin or a DPP4 alone or on a combination of both, or were switched from metformin to DPP4, or were on one of them and the other was added. Let us assume the data shows better glycemic control with a combination of DPP4 with Metformin rather than DPP4 alone. Since the data already exists, it is handed over to a statistician and after the analysis is done, the manuscript writing starts with an objective to submit it to the best journals with the highest impact factor. This is exactly where the plot goes wrong. A simple search might show that there are already numerous studies that have reached the same conclusion. Why would the journal want to publish your data? At the same time, since there are many studies with similar outcomes, it is obvious that despite similar outcomes numerous such studies were published. This is where the study design becomes important. A good way to start is to take a look at the studies with identical outcomes (better glycemic control with a combination of DPP4 and Metformin rather than DPP4 alone) published in the leading journals with high impact factors say in the last 10 years, especially those that have been cited frequently, and to go through the methodologies and limitations of these studies. This is not to replicate the study designs that have been followed but to know what parameters make each of these studies different from each other, although their conclusions appear similar. The outcomes might have been better/poor in some patient profiles than in others or there might be a correlation between the outcomes and some factors. Some examples could be: 1. Age group 2. Male/female sex 3. A particular DPP4 rather than DPP4 as an entire class 4. Region/race/ethnicity of the subjects 5. The number of years since the diagnosis of diabetes 6. Duration of follow-up 7. Associated secondary outcomes like renal function, cardiovascular events, weight loss/gain, lipid profiles, etc. 8. Association with coexisting factors like weight, physical activity, etc at baseline. 9. Pre-existing factors that could have affected the outcomes e.g. hypertension, history of myocardial infarction, etc.

Now with a fair idea of what data is already available and where the gaps are, it might be good to go back to your data and think about what can be the highlight of your study based on the data you have and what is already published. As an example, maybe most studies have included all the DPP4s as an entire class of drugs. Whereas in your data maybe 50-60% of the cohort was on a particular DPP4. That can be the strength rather than the weakness of the study. It might make sense to include only this cohort and leave out the rest so that the strength of the data is robust. Another example – maybe it has been already published that the combination of metformin with DPP4 shows better outcomes in patients who were obese at baseline. Can you make it more specific by analyzing the outcomes by different BMI levels rather than obesity in general? Again, it would depend on your data- what parameters have been monitored and documented that can be used to create a study design that makes a meaningful contribution to research that the journal editors think their readers will be interested in? The flipside here could be that if you filter down the data to such levels, your sample size might become very small, which will discuss in the next paragraph. However, the positive is that you now have a clear focus for your study, which means a higher chance for publication, and if the sample size is small, it is better to wait until you have data from more patients before starting work on the analysis.